The Leader’s Guide to Effective Change Management

We’re reminded daily about how change is coming, and to succeed in business, we must remain agile. That all makes sense in theory, but in practical application, to change how you operate or serve customers is no small feat.

At IMPACT, we’ve gone through quite a bit of change, going from a small core team to a good-sized agency. After struggling to implement a change to our client onboarding process, we decided to take a step back and re-evaluate our approach to change management.

Below, I’ll share with you the key change management models and tools we reviewed, and how you can avoid becoming another statistic.

Why is change management important?

A 2019 Gartner study revealed that most chief human resources officers are unhappy with the speed of change implementation in their organizations.

Why is that? Well, 80% of companies manage change from the top-down, according to the study. With this approach, leadership makes the calls, creates the plan, and sends instructions for company-wide rollout.

While it may seem like the quickest way to implement change, it’s not the best solution in the long term.

Many times, leadership blames employees for unsuccessful changes. However, the data suggests that most employees possess the skills and willingness to undergo organizational changes.

The issue lies in deciding who is part of the strategizing, decision-making, and implementation part of change management.

Today, companies are much more complex and for changes to be effective, they require more input across the organization. In other words, change management should be inclusive.

Change is constant, and developing a model that works for your business is the best way you can manage the people-side of change and set everyone up for success.

4 Common Change Management Models

1. Kurt Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze Model

Picture an ice cube.

Kurt Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze model is exactly what it sounds like.

In the unfreeze stage, you are essentially breaking down the current way of doing business and noting what needs to change. It’s crucial in this stage to obtain two-way feedback of what needs to change (vs. solely top-down).

After noting and communicating the need for change, gather the key stakeholders necessary to proactively implement what needs to be done.

Once everyone has bought in, “re-freeze” to institutionalize the change.

In our experience, this model focuses more on process than people. If you have a smaller team, this could be a good option.

2. The ADKAR® Model of Change

The ADKAR® model breaks down the human side of managing change.

The idea is you should work through each letter of the acronym, focusing heavily on the individuals within your company.

Awareness. Here, the goal is to learn the business reasons for change. At the end of this stage, everyone should be on board.

Desire. This focuses on getting everyone engaged and willingly participating in the change. Once you have full buy-in, the next stage is measuring if the individuals in your company want to help and become part of the process.

Knowledge. In this stage, you’re working toward understanding how to change. This can come in the form of formal training or simple one-on-one coaching so those affected by the change feel prepared to handle it.

Ability. Next, you must focus on how to implement the change at the required performance level. Knowing the required job skills is only the beginning – the people involved need to be supported in the early stages to ensure they can incorporate change.

Reinforcement. Lastly, you need to sustain the change. This final step is often the most missed. An organization needs to continually reinforce change to avoid employees from reverting back to the old way of doing things.

Unlike Lewin’s model, this focuses on the people-side of the stage. We like its idea of using reinforcement to make your changes stick and this model takes it a step further.

It’s a good approach to consider if you have a larger team or a more complex problem you’re trying to solve.

3. Kotter’s 8-Step Model of Change

In his 1995 book, Leading Change, Harvard Business School Professor John Kotter, lays out eight stages all companies must go through to see effective change management.

- Create urgency through open dialogue that leads others in the organization to want the change as much as you.

- Form a powerful coalition of change agents in your organization. This can go beyond leadership.

- Create a vision for change to reinforce the why behind it and the strategy to achieve the end result.

- Communicate the vision regularly to ease team anxiety and reinforce the “why.”

- Remove obstacles to pave the way for the needed changes to happen.

- Create short-term wins to keep up morale and show the team you’re moving in the right direction.

- Build on the change by analyzing what went well and didn’t go so well in your quick wins to keep pushing to the desired end result.

- Anchor the changes in corporate culture as a standard operating procedure, reinforce why change is necessary, and embrace it as part of your company culture.

If you have a more agile team, this model’s iterative process syncs nicely with the agile methodology.

4. Kim Scott’s Get Stuff Done Model

OK, so maybe this one isn’t as common yet, but it soon will be, so you might as well get ahead of the curve.

Kim Scott outlines the GSD model in her bestselling book, Radical Candor, the following process:

- Listen: Listen to your team’s ideas and create a culture where they listen to each other.

- Clarify: Make sure these ideas aren’t crushed before everyone has a chance to understand their potential usefulness.

- Debate: Create an environment where it’s OK to critique, debate, and improve ideas.

- Decide: Select the idea that will best solve the issue.

- Persuade: Since not everyone was involved in the listen-clarify-debate-decide stages, you have to effectively communicate why it was decided and why it’s a good idea.

- Execute: Implement the idea.

- Learn: Learn from the results, whether or not you did the right thing, and start the whole process over again.

We included this in our mix at IMPACT because of how much it focuses on obtaining ideas from the frontline. People buy into what they help create and Kim Scott’s GSD model provides a framework to make that happen.

There are many more models out there for change management and if you’re anything like us at IMPACT, you may take away something valuable from each model and find a combination that works best for your company.

Below is a real example of how my team approached a major change and the steps we took to ensure everyone was moving in the same direction.

1. Determine what needs to change and craft the message.

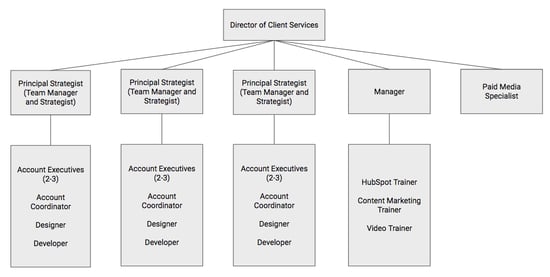

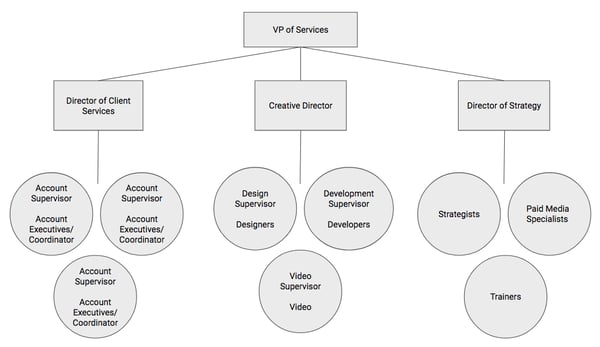

Over the course of three months, IMPACT completely restructured the agency-side of our organization. In March, our agency team looked like this:

This structure worked for us before, but as we came into a new year with an even larger team, our quarterly team survey results told us a different story.

For the first time in several years, not everyone could see their future at IMPACT.

Some had no idea what was going on or why certain decisions had been made. And what stung the most is we had a few happiness scores below seven, which we haven’t had since 2015.

Ouch.

In our February leadership team meeting, we debated for hours why some in the company were feeling this way.

After several ideas, we all determined one area we should focus on was our structure.

We were setting our managers up for failure with competing responsibilities. In doing so, we made it extremely difficult for them to effectively communicate with their teams, coach them in their careers, and ensure they could see their future at IMPACT.

The ones who did better in this area suffered in others, like client results and retention.

It was a huge issue that needed to be solved immediately.

This leadership team meeting was the beginning of step 1 in our change management plan: Determine what needs to change and craft the message.

In our monthly all-hands meeting following that leadership team meeting, our CEO Bob Ruffolo explained the “why” behind our decision.

He explained the survey results, our thought process, and everything that led to the conversation.

Then, he explained that we had outgrown our current structure, placing too much responsibility on our current managers. We inadvertently set up our teams to fail and that wasn’t OK.

To improve this situation, we needed to create a structure that scales.

Planting the seed for a change is just the first step. After this meeting, we knew there would be fear and confusion, so we got to work on step two.

2. Identify your stakeholders and how to manage them.

We knew that a complete structure change would not go well if it was strictly a top-down initiative. We needed help and a core coalition to get it off the ground.

However, not every single person would need to know every single detail of what was going on.

While all teams were involved, most were focused on how they would personally be affected in their day-to-day responsibilities and cross-functional work.

To keep communication clear and ensure everyone a chance to enact Kim Scott’s debate stage, we had to identify stakeholders across the agency team.

In this case, our stakeholders were the team managers. We were essentially changing their job responsibility, so it was essential to include them in the conversation.

Although we created a committee of stakeholders, what we failed to do was take our communication a step further by managing the other agency team members more closely.

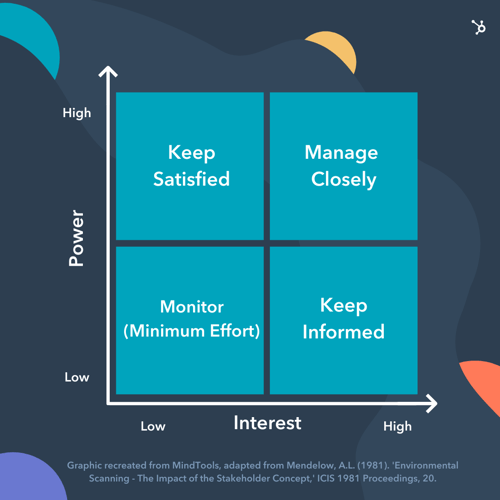

The matrix below outlines a way to segment your team and your communication with each segment so you can better communicate across the board.

We only had our managers involved, and we updated the rest of the team all at once in our monthly all-hands. Next time, we will definitely create a strong communication plan based on this matrix.

Once we identified our key stakeholders, we met with each one and some of their teams to get their feedback, pushback, concerns, and ideas about the structure change.

In full transparency, not all these meetings were fun.

There was high emotion and rigorous debate. However, we had not zeroed in on our exact plan at this point. So, they helped us understand the team’s concerns and ideate on the best way to structure for scale – together.

3. Systematically communicate.

This is an area we got wrong.

In step one, we announced at a company meeting a pretty earth-shattering idea. Our managers felt blindsided and not all the team members were convinced a structure change was needed.

We learned the hard way that surprising people in a company meeting was not the way to go.

Our intention was to be transparent about what was discussed in our leadership team meeting, but there was definitely a better way to do that.

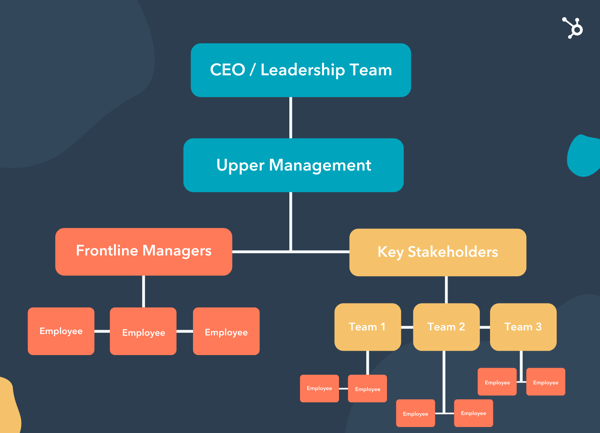

After identifying key stakeholders, this is the path we believe is the best for disseminating information:

Managers can communicate to their own teams in a style that they know will resonate and create shared understanding. They can also help identify issues and concerns so we can all co-create a solution.

This eliminates groupthink and reduces the timeline to extinguish fear.

Although our path was a little messier here, once we received all team feedback, we all agreed to what our new agency structure should be:

Then, we moved on to step four.

4. Get organized with incremental steps.

At this stage, everyone knew a change was coming, but no one knew how we were going to make it happen.

This was the time to get organized and get buy-in on the “how” of change management.

Now that we knew what our new structure would be, we developed a project plan with the incremental steps to get us there by the end of the quarter.

We created a video explaining the structure and project plan for all teams to review in their weekly meetings.

Our managers and key stakeholders were involved and accountable for different parts of the plan, and in our all-hands meetings, we updated on the progress of the plan so everyone could stay informed.

In our plan, we also mapped out some “quick wins” in the first month so the team could feel major progress was happening.

In our case, this was selecting new team managers for the teams whose principal strategists moved over to another team.

We interviewed internally and selected our new managers within three weeks of rolling out our initiative. This was exciting for our new managers and the team to see we were already making huge steps.

5. Equip your managers to handle teams’ emotional responses to change.

It’s great to have good communication and a solid plan but at the end of the day, change is hard.

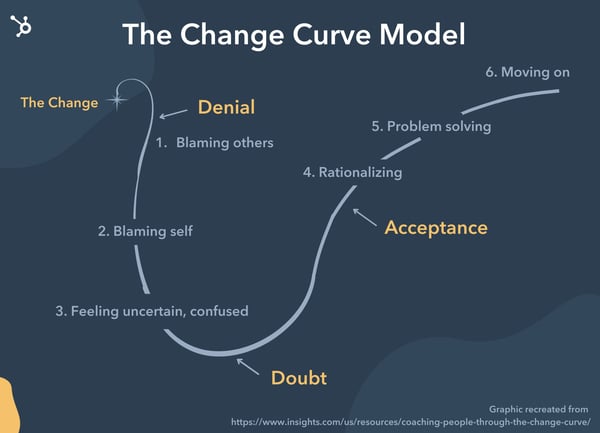

Everyone responds in their own way. What would have been helpful is knowing this concept of The Change Curve.

After our initial all-hands meeting, we had people all over the curve. We then, in essence, said, “Managers, figure it out!”

As we went through the process, we learned another lesson the hard way: We needed to adapt our communication and management style for each individual based on how they were responding to change.

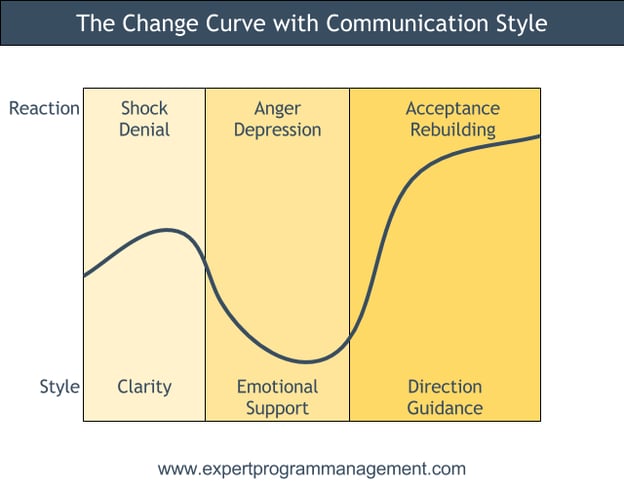

The graphic below illustrates a concept by Expert Program Management, which shows how to change your response along The Change Curve to gain buy-in sooner and give better coaching to your managers.

By meeting team members where they are at, our managers could adapt their communication style to coach each team member through the process, allowing for a more personalized, effective transition.

Keep in mind that this isn’t just advice for managers. Our teams operate in Scrum, and in their team retrospectives, a shared understanding of this tool could have facilitated stronger conversations and better problem-solving.

6. Manage by OKRs.

To stay focused throughout the quarter, we created an objective and corresponding key results (OKRs) for our structure change.

The objective was essentially “Make the structure change happen” and we measured by tracking the milestones from our project plan.

In every all-hands meeting, we updated the team on our efforts using a percentage chart so they could visualize our progress.

This was also a time for those working directly on the project plan to celebrate and give themselves a pat on the back. There was a ton of work involved, and they deserved to be recognized for crushing it.

By breaking down exactly what needed to happen, we were able to keep the team focused and motivated to reach our goal.

7. Continue to prioritize communication.

As I mentioned in step one, discussing the idea is seriously only the first step. To keep everyone motivated, organized, and informed, we had to communicate a lot.

We focused on three types of communication: motivational, informational, and two-way:

- Our motivational communication often came from our CEO to reinforce the “why” behind this major change.

- Informational communication came from updates on our OKRs in our all-hands meetings, as well as one-off videos from the team working on the project plan to update on progress.

- Two-way communication was (and is) arguably the most important one. We started off slow in this area, but after getting feedback in our Q2 team survey and from people on the team, we doubled down on this much more in the last month of the transition.

A regular cadence of two-way communication means your team understands what’s being shared, but you also learn and address if there’s underlying dissent or miscommunication.

Although I put this as the last step, it’s the most crucial.

Communication must happen throughout your entire initiative or you’ll risk falling short and potentially damaging company morale in the process.

If you focus on the three types of communication above, you will reach your goals faster with a happier team to boot.

Why is change management important?

There is rarely a beginning and a clear-cut end like the more traditional models. I’m sure we’ll discover more tweaks we need to get our structure right, and that’s OK.

As a leader, you can choose a model, or a mix of models like what we do at IMPACT, to help organize effective, lasting change in your organization.

By incorporating your team via the communication methods outlined above, you can empower and enable your team to take action – and have pride in the change they helped make.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published in November 2018 and has been updated for comprehensiveness.

![]()

![Download Now: 2021 State of RevOps [Free Report]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/53/78dd9e0f-e514-4c88-835a-a8bbff930a4c.png)